Christopher Kempf, the statistical analyst of the PDC, takes a look at why the 132 finish is a favourite amongst darts fans.

It is not the highest checkout in darts, nor the most difficult.

Yet 132 holds a certain mystique in the darts world unrivalled by that of any other checkout.

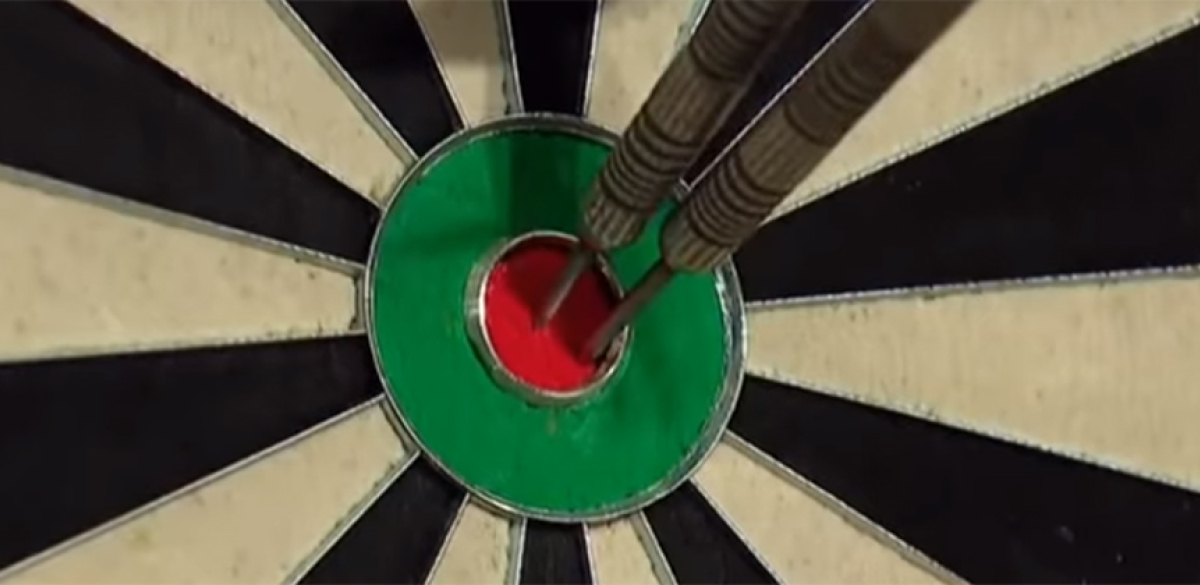

For many years it was the subject of the most viewed video of professional darts on YouTube, in which Phil Taylor defeated James Wade in 2008 World Matchplay final with a masterful covered-bull shot to complete a 132 finish.

“Annie Oakley couldn't hit this with her best rifle...but The Power can!” said Sid Waddell.

It also represents a celebrated moment in the career of Michael van Gerwen, who permanently dethroned Taylor as Premier League champion in 2013 under immense pressure with a 25 - treble 19 - bullseye outshot.

The bullseye-bullseye-double 16 route, hit on stage most recently by Ryan Joyce in Copenhagen, is one of the best-known and best-loved exhibition checkouts a fan can witness in a match.

What makes the 132 unique is the unusually large array of plausible routes a player attempting the checkout can choose from.

For many other three-figure checkouts, players are limited to one or two sensible combinations of trebles and doubles with which to complete the finish, but there are at least eight available when attempting 132.

This is the only checkout in which two bullseyes, two trebles or two doubles can be used to complete it, and for which there are plausible routes for any of the above that minimize the need to switch and do not require the use of unfamiliar segments.

EXPECTED CHECKOUT PROBABILITY IN THREE DARTS (by individual route only)

Based on PDC-wide stage accuracy percentages for individual segments

T20 - D18 - D18 6.7%

T20 - D20 - D16 6.6%

T20 - T20 - D6 5.7%

T18 - T18 - D12 5.4%

25 - T19 - Bull 5.2%

T20 - T16 - D12 5.1%

T16 - T16 - D18 4.9%

Bull - T14 - D20 3.2%

Bull - Bull - D16 2.3%

Despite this diversity of choice, about 80% of players in stage events throw for the bullseye first, with the result that a large majority of completed 132 checkouts are accomplished via the 25 - treble 19 - bullseye route.

Even when the bullseye is hit with that first dart, players will rarely opt for the easier treble 14 - double 20 route from 82, choosing to check out with flair and attempt to squeeze two darts into the smallest segment on the board.

While the combined probability from scoring either 25 or 50 with the first dart results in an overall 7.6% checkout probability when this route is chosen, this calculation does not factor in the unpredictable possibility of a dart blocking the bullseye or increasing the risk of a bounce-out.

Dave Chisnall's 132 attempt against Raymond van Barneveld in the 2017 World Cup illustrates this well; his second dart thrown at the bull was precisely on target, but collided with the first dart and the wire, fell to the floor, and ended Chisnall’s chances of winning the leg.

The temptation to checkout in style is often too great to resist.

Why do players, especially those who are skilled at hitting many of the segments integral to the alternative routes, attempt the riskiest and most challenging checkout route every time, almost without fail?

To the extent that darts players view themselves as entertainers as well as competitors, they may believe that the fans, by virtue of having paid to watch the match, are entitled to see at least an attempt at an exhibition checkout.

It is common to see these attempts made even when a player's opponent is not waiting on a finish.

Intriguingly, some players may even view attempting the rarer double-double routes (T20 D18 D18, for instance) to be an arrogant gesture, even with respect to the flashy but standard bullseye route and in circumstances where a checkout in three darts is essential.

The various 132 checkout options call into question what should be considered acceptable competitive play, and emphasise that the double-double options, for this and other finishes like 137 and 140, are more sensible than they appear.

With a 4% PDC-wide completion rate, the 132 finish is generally rare enough that dozens of failed attempts and hundreds of legs often separate successful finishes, but common enough that one would expect to see the finish hit at least once in any given tournament.

It is common but not ubiquitous, difficult but universally accessible.

Many players could benefit from having alternative routes to the 132 finish in their retinue.

But there is no doubt that watching professionals bend and slide darts into the bullseye like snooker balls and manoeuvre deftly around blockers, at the risk of watching one or both darts fall to the floor, is one of the great thrills of the game, and one almost unique to the fascinating 132 checkout.

Follow Christopher Kempf on Twitter through @Ochepedia